Marine

- Additives & Supplements

- Aquarium Controllers

- Aquariums & Accessories

- ATO & Dosing Pumps

- Filters & Filter Media

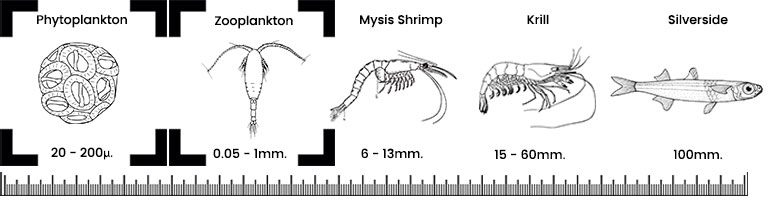

- Fish & Coral Foods

- Fragging Supplies

- Heater & Chillers

- Lighting

- Maintenance Tools

- Medications, Pest & Algae Control

- Plumbing Parts

- Protein Skimmer

- Pumps, Powerhead & Accessories

- Reactors

- RO/DI Reverse Osmosis

- Rocks, Sand & Aquascape Tools

- Salt Mix & Maintenance Tools

- Test Kits

- UV Sterilizers